Some background: Vans first filed suit against MSCHF in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District for New York in April 2022, alleging that the Brooklyn-based art collective-slash-sneaker maker was willfully infringing its trademark rights in the 40-year-old OLD SKOOL shoe. MSCHF responded by arguing that its offerings, including the Wavy Baby sneakers, “are not mere consumer goods,” but instead, are “an expression protected by the First Amendment.” (MSCHF has also taken issue with the scope of Vans’ trademark rights, including in the OLD SKOOL sneaker design.)

Judge William Kuntz of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York handed Vans an early victory shortly after the suit was filed by putting a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction in place to block MSCHF from promoting its allegedly infringing Wavy Babys by displaying the shoes on its website, mobile app, and in art exhibitions, among other things. The court’s decision prompted an appeal from MSCHF, which argued that the district court erred in concluding that Vans was likely to succeed on the merits of its trademark infringement claim (and not applying the Rogers test factors) because Vans’ claims are precluded by the First Amendment. More than that, MSCHF maintained that the district court’s injunction prohibiting it from advertising the Wavy Baby shoes amounts to “an unconstitutional prior restraint of speech.”

In a per curiam opinion, Judges Dennis Jacobs, Denny Chin, and Beth Robinson set the stage, stating that “the central issue in this case is whether and when an alleged infringer who uses another’s trademarks for parodic purposes is entitled to heightened First Amendment protections, rather than the Lanham Act’s traditional likelihood of confusion inquiry.” The court also stated up front that “the main issues in this appeal are governed by the … recent decision in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC,” in which the Supreme Court held that “when an alleged infringer uses a trademark as a designation of source for the infringer’s own goods, the Rogers test does not apply.” This is true, according to the Second Circuit, “even if an alleged infringer used another’s trademarks for an expressive purpose.”

Rogers Test or Polaroid Factors – To evaluate whether the district court erred in concluding that Vans was likely to succeed on its infringement claim, the Second Circuit first considered whether the Wavy Baby shoes are subject to a traditional likelihood of confusion analysis or whether they amount to an expressive work entitled to heightened First Amendment scrutiny under Rogers v. Grimaldi.

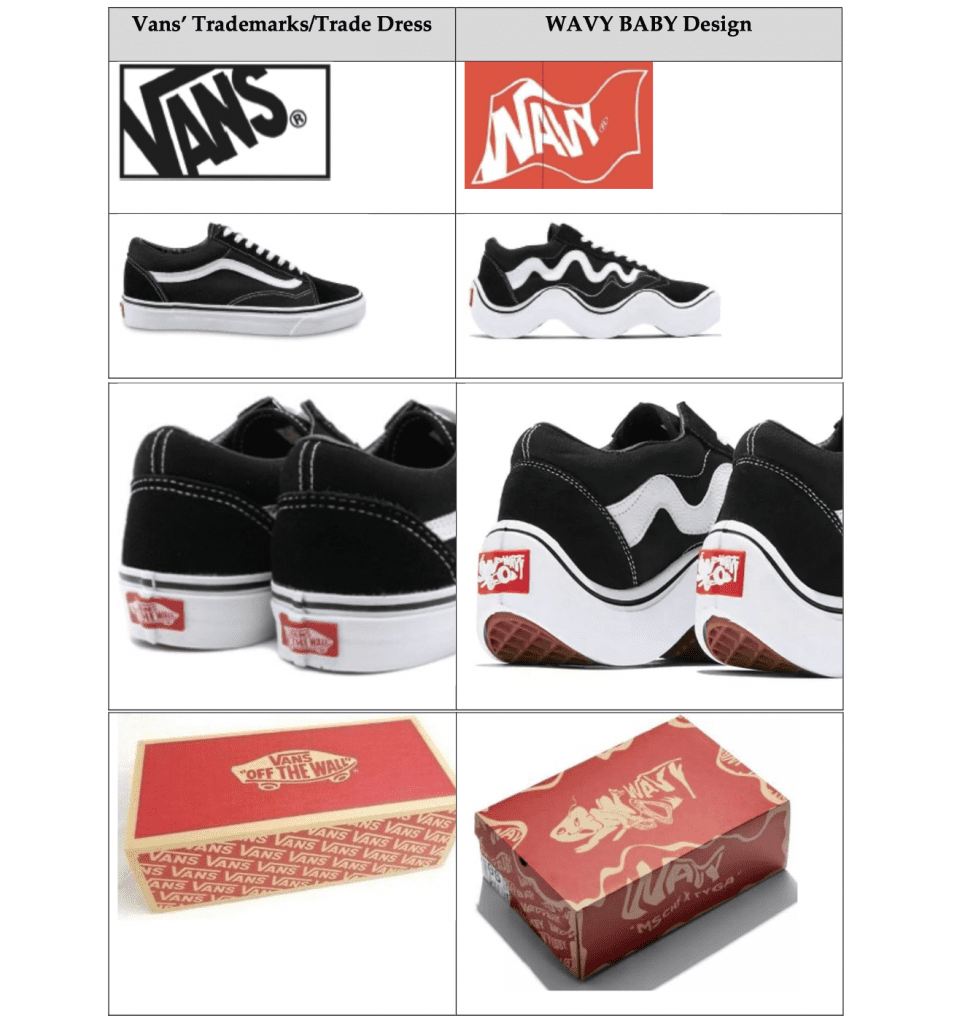

The appeals court concluded that the Supreme Court’s decision in Jack Daniel’s “forecloses MSCHF’s argument that [the] Wavy Baby’s parodic message merits higher First Amendment scrutiny under Rogers,” as MSCHF used Vans’ marks “in much the same way that VIP Products used Jack Daniel’s marks – as source identifiers.” Specifically, MSCHF’s design “evoked myriad elements of the Old Skool trademarks and trade dress,” including “the Old Skool black and white color scheme, the side stripe, the perforated sole, the logo on the heel, the logo on the footbed, and the packaging.” And “unlike VIP Products,” the Second Circuit noted that “MSCHF did not include a disclaimer disassociating it from Vans or Old Skool shoes.”

Moreover, the court pin-pointed language from MSCHF, which revealed that it opted to make use of Vans’ marks because “[n]o other shoe embodies the dichotomies – niche and mass taste, functional and trendy, utilitarian and frivolous – as perfectly as the Old Skool,” as indicative of the fact that “MSCHF sought to benefit from the ‘good will’ that Vans had generated over a decades-long period.” As such, and “notwithstanding the Wavy Baby’s expressive content,” the court found that “MSCHF used Vans’ trademarks in a source-identifying manner,” and thus, the district court was correct to apply the traditional likelihood-of-confusion test instead of the Rogers test.

Applying the Polaroid factors as part of the traditional likelihood-of-confusion test, the Second Circuit held, in part …

(1) Strength of the Marks – “The strength of the marks at issue supports Vans. MSCHF expressly chose the Old Skool marks and dress because it was the ‘most iconic, prototypical’ skate shoe there is, as conceded by MSCHF’s co-Chief Creative Officer.”

(2) Similarity – “The similarity of the marks presents a closer question, as the marks on Wavy Baby, while derived from the Old Skool shoes, are distorted.” Vans has “never warped its design in the same … manner as MSCHF’s work with the Wavy Baby.” But the court held that it is relevant that “Vans has previously created special editions of its Old Skool sneaker often collaborating in launching the sneakers with celebrities and high-profile brands.”

(3) Market Proximity – “Considering the Wavy Baby as a wearable sneaker, we agree with the district court that the shoes are relatively proximate.” The Second Circuit said that “although it is hard to see why some people would wear the Wavy Baby as a functional shoe,” it noted that MSCHF “advertised the Wavy Baby as a wearable piece of footwear in promotional posts and in the promotional [Tyga] music video.” (The court also stated that “many people are martyrs to fashion and dress to excite comment” in a nod to its finding that the Wavy Baby sneaker is in close proximity to Vans sneakers.)

The court also noted relatively similar price points between the limited-edition $220 Wavy Babys and Vans sneakers that “sometimes selling for $180 per pair, and often [come in] a limited edition of 4,000 units.”

(4) Likelihood of Confusion – The court cited “evidence in the record that customers were actually confused.” Moreover, while “it may be true that consumers who purchase the Wavy Baby shoes directly from MSCHF and receive the accompanying ‘manifesto’ explaining the genesis of the shoes may not be confused,” the Second Circuit noted that the Lanham Act also protects against post-sale confusion. The Second Circuit also stated that the lower court relied on evidence of actual confusion, including comments made on a sneaker-centric podcast.

(5) Sophistication of the Buyers – The Second Circuit held that the district court was correct to conclude that “sophistication of the buyers also favored Vans,” as MSCHF engaged in “broad advertising to the ‘general public,’ and customers of sneakers are not professional buyers.”

A Note on Parody – With the foregoing in mind, the court stated that “the fact that the Wavy Baby was conceived as a parody does not change that assessment,” noting that the Wavy Baby “is a parody, just not one entitled to protection under Rogers.” In order to be successful, a parody “must create contrasts with the subject of the parody so that the ‘message of ridicule or pointed humor comes clear,” the Second Circuit stated, citing Jack Daniel’s. “If that is done, ‘a parody is not often likely to create confusion’ … but if a parodic use of protected marks and trade dress leaves confusion as to the source of a product, the parody has not ‘succeeded’ for purposes of the Lanham Act, and the infringement is unlawful.”

For these reasons, among others, the court concluded that the Wavy Baby “does create a likelihood of consumer confusion, and the district court correctly concluded that Vans is likely to prevail on the merits.” As such, it further held that the lower court “did not exceed its discretion by enjoining MSCHF’s marketing and sale of the Wavy Baby.”

The case is Vans Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio Inc., 22-1006 (2d. Cir.).