The COVID-19 pandemic, along with the continued global rise in chronic illness and related disease risk factors, such as obesity, high blood sugar, and outdoor air pollution exposures, seen over the past 30 years has created a ‘perfect storm’, fueling COVID-19 deaths, says a new study published Thursday in The Lancet .

The global disease estimates provide insights into how rising chronic disease, along with public health failures, is fueling excess deaths from SARS-CoV-2 among people with pre-existing conditions.

Led by the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) is a comprehensive global study, analyzing and ranking 286 causes of death, 369 disease and injuries, and 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories.

The GBD study, covering 204 countries, also tracks a population’s social and economic status on the basis of socio-demographic index (SDI). SDI combines information on average income per capita, educational attainment, and total fertility rates.

Increased COVID-19 Illness and Death Associated With NCDs & NCD Risk Factors

The study found that increased illness and death from COVID-19 is associated with several risk factors and non-communicable diseases, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, as well as outdoor air pollution exposures.

But these diseases don’t just interact biologically, they also interact with socioeconomic factors, the study highlights. Underlying social inequities that perpetuate chronic diseases need to be addressed through policy and research in order to prevent the burden of disease from worsening and leaving populations vulnerable to increased risk of COVID-19, the study concludes.

Said Dr Richard Horton, Editor-in-Chief of The Lancet: “The syndemic nature of the threat we face demands that we not only treat each affliction, but also urgently address the underlying social inequalities that shape them—poverty, housing, education, and race, which are all powerful determinants of health.”

He continues, “COVID-19 is an acute-on-chronic health emergency. And the chronicity of the present crisis is being ignored at our future peril. Non-communicable diseases have played a critical role in driving the more than 1 million deaths caused by COVID-19 to date, and will continue to shape health in every country after the pandemic subsides. As we address how to regenerate our health systems in the wake of COVID-19, this Global Burden of Disease Study offers a means of targeting where the need is greatest, and how it differs between countries” .

An accompanying Lancet editorial “Global Health: time for radical change” also states: “The message of GBD is that unless deeply embedded structural inequities in society are tackled and unless a more liberal approach to immigration policies is adopted, communities will not be protected from future infectious outbreaks and population health will not achieve the gains that global health advocates seek. It’s time for the global health community to change direction.”

The study also reveals that the rise in exposure to key risk factors (including high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high body-mass index [BMI], and elevated cholesterol), combined with rising deaths from cardiovascular disease in some countries (e.g., the USA and the Caribbean), suggests that the world might be approaching a turning point in life expectancy gains.

The authors stress that the promise of disease prevention through government actions or incentives that enable healthier behaviours and access to health-care resources is not being realised around the world.

“Most of these risk factors are preventable and treatable, and tackling them will bring huge social and economic benefits. We are failing to change unhealthy behaviours, particularly those related to diet quality, caloric intake, and physical activity, in part due to inadequate policy attention and funding for public health and behavioural research”, says Professor Christopher Murray, Director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, USA, who led the research.

“Double Down” on Development Promotes Health – Address NCDs in Low & Middle Income Countries

The report also contains some good news. Over the past two decades, since the adoption of the UN Millennium Development Goals, low and low-middle income countries have chalked up faster progress in their socio-demographic index (SDI), in comparison to rich countries, the report finds. Such progress is “highly correlated” with better health outcomes as well.

“Given the overwhelming impact of SDI on health progress, doubling down on policies and strategies that stimulate economic growth, expand access to primary and secondary schooling, and improve the status of women should be our collective priority,” adds Murray.

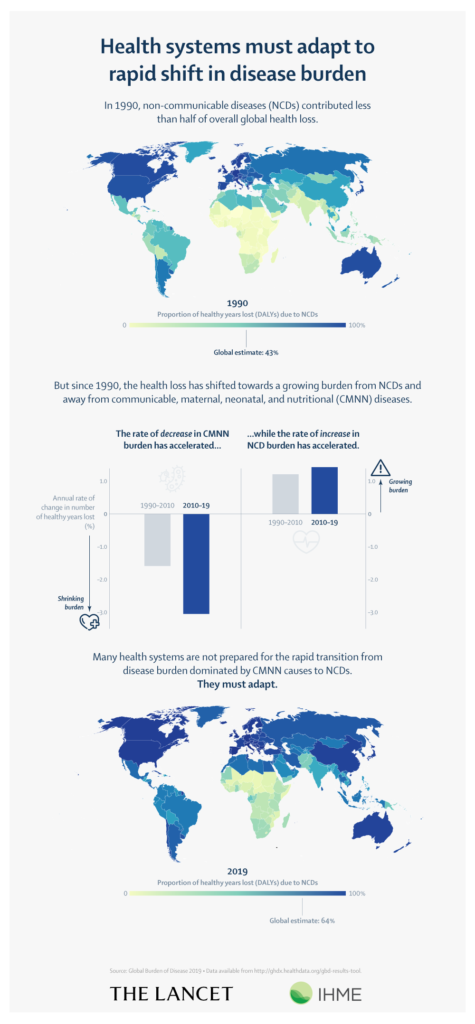

However, LMICs are not prepared to handle the growing transition in the disease burden from communicable diseases to non-communicable diseases (NDCs), the report also finds.

Indeed, most global health policy discussion, including that of WHO, still focuses on communicable diseases, “even though there is an inevitable shift of disease burden to non-communicable disease.”

[huge_it_slider id=”15″]

‘Functional Disorders’ – A Growing Problem

Another challenge low- and middle-income countries may face, in particular, is the loss of so-called “functional health” capacities, which may not be well represented in classic health metrics characterizations of so-called “premature disability (DALY’s)”, the report notes.

This can include issues such as: musculoskeletal disorders, mental disorders, substance misuse, vision loss, and hearing loss – issues which also become more acute as people live to older ages. Instead, current policy discussion is primarily focused on cardiovascular diseases and cancers, with low investment in research towards understanding underlying causes and therapeutic solutions for functional health loss.

Health of Children Has Seen Steady Improvement; Not So for Older Age Groups

While global health has still steadily improved over the past 30 years, especially for children under 10 years old, thanks to improvements in prenatal care and efforts to tackle infectious diseases, the same cannot be said for older age groups.

Worldwide health loss, measured in disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), is increasing. Six of the causes primarily affect older adults (ischaemic heart disease, diabetes, stroke, chronic kidney disease, lung cancer, and age-related hearing loss) and the other four are common from teenage years into old age (HIV/AIDS, other musculoskeletal disorders, low back pain, and depressive disorders).

Though the number of DALYs hasn’t increased, there are a greater number occurring at old age. There has been a global shift towards non-communicable diseases and injuries, with them being half of the disease burden for 11 countries in 2019. However, global public health has focused more on primary causes of death rather than the systemic disparities of health, such as inequalities in access to preventative and curative services for lower socioeconomic groups.

As said in the GBD: “Policy makers should remain aware that the number of DALYs represents the burden of disease that the world’s health systems must manage.” Health relies on more than just health systems.

Air Pollution among the Fastest Increasing Health Risks

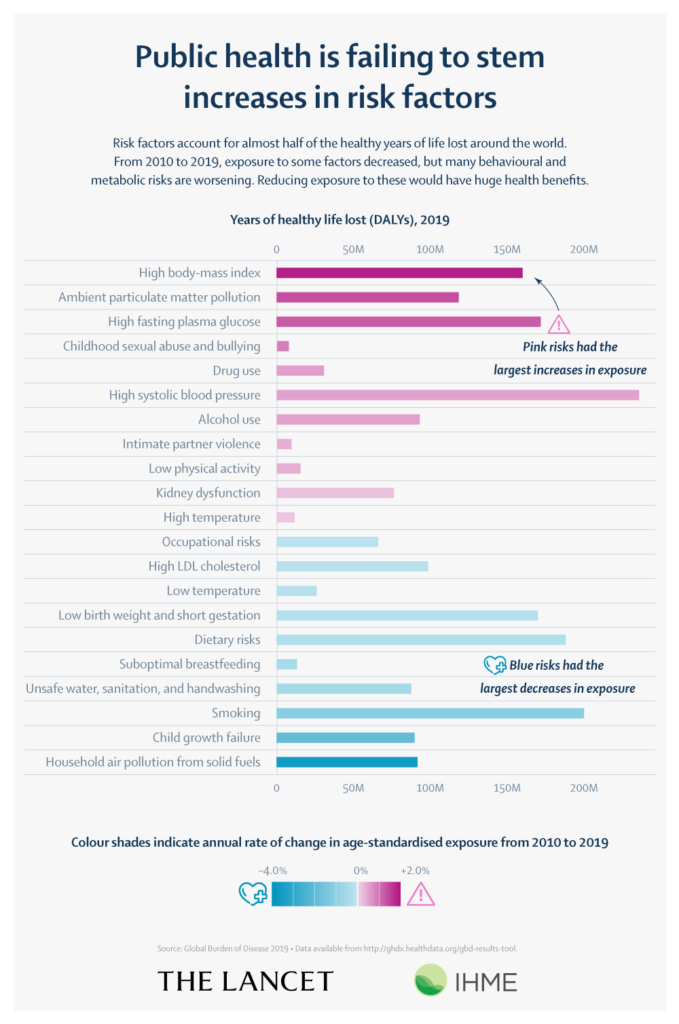

GBD research has also shown that ambient air pollution (from particulate matter) was one of the fastest growing ‘health risks’, along with drug use, high fasting plasma glucose, and high body mass index (BMI) by more than 0.5% per year. Many health risks are considered preventable and can be slowed down and reversed through public health action and policy.

Risks that are strongly linked to social and economic development were the largest declines in risk exposure from 2010 to 2019. These included household air pollution; unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing; and child growth failure. This correlates to increasing global SDI. Global declines were also reported for tobacco smoking and lead exposure.

The decrease in tobacco smoking, down 1-2% per year since 2010, is a partial success due partly to the governmental interventions and policy on tobacco control. In comparison, there has been inadequate policy and attention dedicated to BMI, one of the leading causes to contributable DALYs.

Speaking about the findings, Murray says, “Governments should invest more funding in research and action to tackle these stagnating or worsening risk exposures. A core obstacle to accelerating progress on behavioural risks is the notion of individual agency and the need for governments to let individuals make their own choices.

“This concept is naïve, given that individual choices are influenced by context, education, and availability of alternatives. Governments can and should take action to facilitate healthier choices by rich and poor individuals alike. When there is a major risk to population health, concerted government action through regulation, taxation, and subsidies, drawing lessons from decades of tobacco control, might be required to protect the public’s health.”

Image Credits: Igbarrio, The Lancet/IHME.