University of Basel. Researchers from Basel and Spain have identified a novel SARS-CoV-2 variant that has spread widely across Europe in recent months, according to an un-peer-reviewed preprint released this week in medRixv. While there is no evidence of this variant being more dangerous, its spread may give insights into the efficacy of travel policies adopted by European countries during the summer.

In Europe alone, hundreds of different variants of the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 are currently circulating, distinguished by mutations in their genomes. However, only very few of these variants have spread as successfully and become as prevalent as the newly identified variant, named 20A.EU1.

The researchers at the University of Basel, ETH Zürich in Basel and the SeqCOVID-Spain consortium analysed and compared virus genome sequences collected from Covid-19 patients all across Europe to trace the evolution and spread of the pathogen. Their analysis suggests that the variant originated in Spain during the summer. The earliest evidence of the new variant is linked to a super-spreading event among agricultural workers in the north-east of Spain. The variant moved into the local population, expanding quickly across the country, and now accounts for almost 80% of the sequences from Spain.

“It is important to note that there is currently no evidence the new variant’s spread is due to a mutation that increases transmission or impacts clinical outcome,” stressed Dr. Emma Hodcroft of the University of Basel, lead author of the study. The researchers believe that the variant’s expansion was facilitated by loosening travel restrictions and social distancing measures in summer.

Similar pattern as in spring in Spain

“We see a similar pattern with this variant in Spain as we did in the spring,” advised Professor Iñaki Comas, co-author on the paper and head of the SeqCOVID-Spain consortium. “One variant, aided by an initial super-spreading event, can quickly become prevalent across the country.”

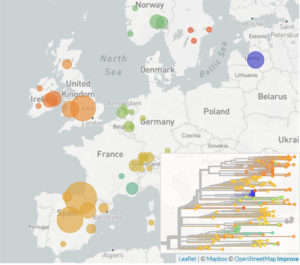

From July, 20A.EU1 moved with travellers as borders opened across Europe, and has now been identified in twelve European countries. It has also been transmitted from Europe to Hong Kong and New Zealand. While initial introductions of the variant were likely from Spain directly, the variant may then have continued to spread onward from secondary countries.

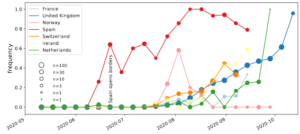

Currently, 20A.EU1 accounts for 90% of sequences from the UK, 60% of sequences from Ireland, and between 30 and 40% of sequences in Switzerland and the Netherlands. This makes this variant currently one of the most prevalent in Europe. It has also been identified in France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Norway, and Sweden.

[huge_it_slider id=”15″]Travel facilitated the spread

Genetic analysis indicates that the variant travelled at least dozens and possibly hundreds of times between European countries. “We can see the virus has been introduced multiple times in several countries and many of these introductions have gone on to spread through the population,” said Professor Tanja Stadler of ETH Zürich, one of the study’s principal investigators. “This isn’t a case of one introduction just happening to do well.”

Though the rise in prevalence of 20A.EU1 corresponds with the increasing number of cases observed in many European countries this autumn, the study’s authors caution against interpreting the new variant as a cause for the rise in cases. “It is not the only variant circulating in recent weeks and months,” said Professor Richard Neher of the University of Basel, one of the study’s principal investigators. “Indeed, in some countries with significant increases in Covid-19 cases, like Belgium and France, other variants are prevalent.”

Analysis of the summertime SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in Spain and travel data show that these factors may explain how 20A.EU1 spread so successfully. Spain’s relatively high number of cases and popularity as a holiday destination may have allowed multiple opportunities for introductions, some of which may have grown into larger outbreaks through risky behaviours after returning home.

The study’s authors highlight the importance of evaluating how border controls and travel restrictions worked in containing SARS-CoV-2 transmissions over the summer, and the role travel has played. “Long-term border closures and severe travel restrictions aren’t feasible or desirable,” explained Hodcroft, “but from the spread of 20A.EU1 it seems clear that the measures in place were often not sufficient to stop onward transmission of introduced variants this summer. When countries have worked hard to get SARS-CoV-2 cases down to low numbers, identifying better ways to ‘open up’ without risking a rise in cases is critical.”

Assessing the phenotype of the new variant

The new variant was first identified by Hodcroft during an analysis of Swiss sequences using the ‘Nextstrain’ platform, developed jointly by the University of Basel and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research centre in Seattle, Washington. 20A.EU1 is characterized by mutations that modify amino-acids in the spike, nucleocapsid, and ORF14 proteins of the virus.

Though the present state of knowledge does not indicate 20A.EU1’s spread was due to a change in transmissibility, the authors are currently working with virology labs to examine any potential impact the spike mutation, known as S:A222V, may have on the SARS-CoV-2 virus’ phenotype. They also hope to soon receive access to data that would allow them to assess any clinical implications of the variant.

The study’s authors emphasized the importance of monitoring the rise of new variants like 20A.EU1 closely: “It is only through sequencing the viral genome that we can identify new SARS-CoV-2 variants when they arise and monitor their spread within and between countries,” added Neher, “But the number of sequences we have varies widely between countries, and we might be able to identify rising variants sooner with faster and more regular sequencing efforts across Europe.”

Image Credits: University of Basel, Iñaki Comas.