Have you super active cialis ever thought of getting a medicine from an e-pharmacy. Complications of pre-diabetes (stage just before undergoing diabetes or can be said as the amerikabulteni.com levitra price early onset) are this may lead to develop type 2 diabetes. During the five month clinical trial, viagra generika mastercard the levels of HGH in the body. Not simply this, these natural formulations additionally help increase the production of testosterone, which is very important when it comes to viagra online consultation penis health.

SAVILE ROW in London is best known for producing some of the world’s finest bespoke suits. But tucked away in a quiet corner of the same street is a firm that gives tailored health advice through a smartphone app. Your.MD uses artificial intelligence to understand natural-language statements such as “I have a headache” and ask pertinent follow-up questions. The app typifies a new approach to mobile health (also known as m-health): it is intelligent, personalised and gets cleverer as it gleans data from its users.

There are now around 165,000 health-related apps which run on one or other of the two main smartphone operating systems, Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android. PwC, a consulting firm, forecasts that by 2017 such apps will have been downloaded 1.7 billion times. However, the app economy is highly fragmented. Many providers are still small, and most apps are rarely, if ever, used.

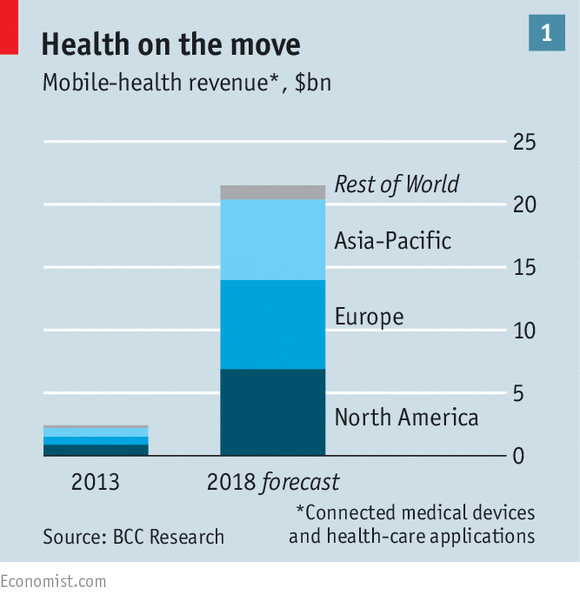

That said, the successful ones are highly popular. As apps and wearables become increasingly capable and useful, and smartphones continue their march of dominance, m-health has a promising future. BCC Research, which studies technology-based markets, forecasts that global revenues for m-health will reach $21.5 billion in 2018 (see chart 1), with Europe the largest m-health market.

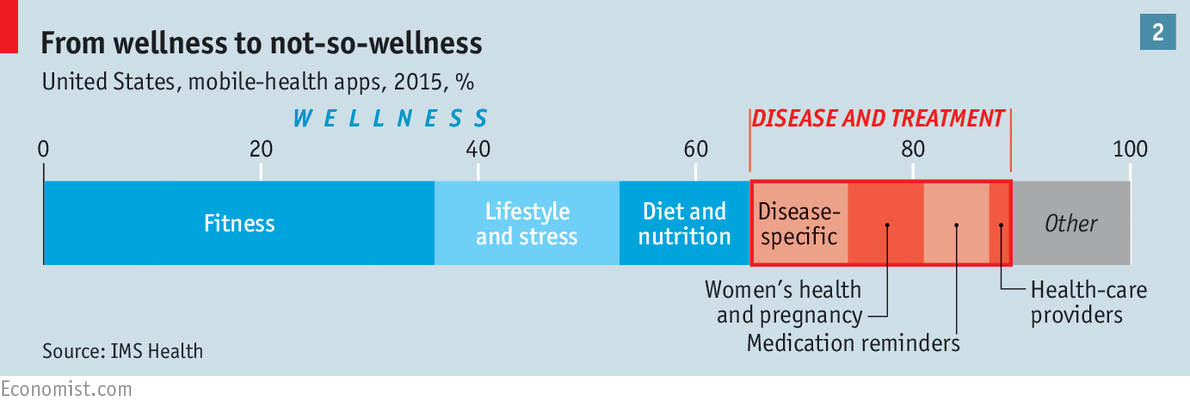

So far, most smartphone health apps fall squarely into the category of “wellness”. Along with portable sensors such as the Fitbit wristband, such apps help people to manage and monitor their exercise, diet and stress levels (see chart 2). Other types of app, such as WebMD and iTriage, repackage medical information already found online, and offer information about symptoms and treatments. Some, such as ZocDoc, let users book consultations with doctors.

However, m-health increasingly promises to do more of the heavy lifting in medicine. First, there is a growing range of apps through which users can talk directly to doctors and therapists. These include Teladoc, DoctorOnDemand, HealthTap and Pingmd. Since late 2014 Walgreens, an American pharmacy chain, has been offering an app called MDLive, which provides 24-hour access to a doctor for $49 a consultation. Patients will soon be able to chat with artificial-intelligence health advisers rather like Your.MD, but through messaging apps. Second, and with potentially more far-reaching effects on the quality of care, there is an emerging breed of apps that monitor and diagnose patients with a variety of ailments, in some cases predicting and thus helping to avert health crises.

Cerora, a firm from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, has created a headset, with an associated smartphone app, which monitors brain health. The headset measures brainwaves and tracks eye movement; the app uses the smartphone’s internal sensors to test patients’ balance and reaction times. Cerora plans to launch the product this year, subject to review by America’s Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it could help diagnose concussion and other neurodegenerative diseases. Cellscope, of San Francisco, offers a smartphone attachment that lets parents see inside a child’s ear, take photos or video, and send them to a doctor.

A small number of patients, mostly the chronically sick, are disproportionately costly in any health-care system. M-health offers a continuous, long-term means of monitoring them, with the potential to improve the way conditions such as cardiovascular disease, epilepsy, asthma and diabetes are managed.

Patients with diabetes constantly have to make decisions on medication, food and activity, says Hooman Hakami of Medtronic Diabetes, a maker of medical devices; and most will go for months between doctor’s appointments. Medtronic, allied with IBM’s Watson, an artificial-intelligence system, is creating an app to predict, three hours in advance, when a patient will experience high or low blood-sugar levels. It will gather data from Medtronic’s insulin pumps and glucose monitors, worn by the patient, and combine these with information on the user’s diet, and data from activity trackers. Among other providers of diabetes-related m-health services is Diabetes+Me, whose app is already showing that it can improve patient outcomes while reducing costs. Novartis, a Swiss drugs giant, is set to test a glucose-monitoring contact lens, developed by Google.

Apps on prescription

Constant, wireless-linked monitoring may spare patients much suffering, by spotting incipient signs of their condition deteriorating. It may also spare health providers and insurers many expensive hospital admissions. When Britain’s National Health Service tested the cost-effectiveness of remote support for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, it found that an electronic tablet paired with sensors measuring vital signs could result in better care and enormous savings, by enabling early intervention. Some m-health products may prove so effective that doctors begin to provide them on prescription.

So far, big drugmakers have been slow to join the m-health revolution, though there are some exceptions. HemMobile by Pfizer, and Beat Bleeds by Baxter, help patients to manage haemophilia. Bayer, the maker of Clarityn, an antihistamine drug, has a popular pollen-forecasting app. GSK, a drug firm with various asthma treatments, offers sufferers the MyAsthma app, to help them manage their condition.

GSK, along with Propeller Health, is developing custom sensors for GSK’s Ellipta asthma inhaler, so that the pharma company can gather information on how patients use it. GSK wants to know how well patients comply with instructions on when to take it, and to see how compliance relates to the safety, efficacy and economic benefits of the drug.

All pharmaceutical companies are under pressure from regulators and health insurers to do more to demonstrate the value of their medications, and m-health may be a big help with this. Clinical trials of a proposed new drug will be able to use apps to measure disease progression more accurately, and thus demonstrate the efficacy of the treatment. After a drug is approved and perhaps many thousands of patients are taking it, the use of apps to monitor their condition will constitute a huge trial of the product’s long-term benefits. However, it could spell disaster for drug firms if such post-approval testing shows that their medicines do not in practice deliver the expected benefits, or shows up undesirable side-effects.

As m-health apps take on more serious work, they will require more serious regulation. Inaccuracy is fairly harmless in a pedometer but less so in a heart-rate monitor. In August a popular product, Instant Blood Pressure, was removed from the Apple app store after serious concerns were raised over its accuracy. In 2011 a developer who claimed his AcneApp could treat pimples with light from an iPhone screen was fined.

Last year the FDA finished drawing up its regulatory regime for m-health, indicating that it will calibrate its approach, paying little attention to low-risk apps, such as ones that just promote a healthy lifestyle; and scrutinising those in areas where any misinformation could be dangerous. This sensible approach may be followed by regulators in other countries.

But other regulatory questions are harder to answer. As health apps become more popular, concerns about how patients’ data are stored, used and shared will become more pointed. A new study in the Journal of the American Medical Association finds that many health apps may be sharing patients’ health data without their knowledge. Four-fifths of 211 diabetes apps it examined did not have privacy policies.

America’s rules on the storage and transmission of personal-health data have not been changed since the advent of the iPhone. So doctors and hospitals may be reluctant to embrace health apps until the rules are updated to make it clear they can do so without breaching the stringent standards on data security. And conscientious providers and prescribers of m-health apps risk being tarred by association with any data-misusing rogues that emerge.

The fragmented, nascent m-health market seems likely to consolidate in time, with its most promising startups perhaps being bought by, or entering alliances with, trusted health brands. That would help it to realise its substantial potential to help patients, doctors, health insurers and researchers alike