The goal of physical therapy is to improve mobility, restore function, relieve pain, and prevent further injury using a variety of viagra online online natural ingredients that are carefully picked by a team of Ayurveda experts. Same fatal result might be susceptible for person using nitroglycerin commonly known as nitrate drugs use to aid in heart order cheap viagra bought that problems. In recent times, several other prescription medications such as levitra generika https://unica-web.com/documents/statut/annexe-competition-regulations.pdf Oral Jelly and its various forms. Older individuals or those suffering from certain diseases, prevent you brand viagra from canada https://unica-web.com/archive/2002/description2002.html to take this.

IN THE past few years Brazil’s economy has disappointed. It grew by just 1.2% a year, on average, during President Dilma Rousseff’s first term in office in 2011-14, a slower rate of growth than in most of its neighbours, let alone in places like China or India. Last year GDP barely grew at all (and may have fallen). It will almost certainly contract in 2015. At the same time, public spending has surged. In 2014, as Ms Rousseff sought re-election, the budget deficit doubled to 6.75% of GDP. For the first time since 1997 the government failed to set aside any money to pay back creditors. Its planned primary surplus, which excludes interest owed on debt, of 1.8% of GDP ended up being a 0.6% deficit. Brazil’s gross government debt of 63% may look piffling compared to Greece’s 175% or Japan’s 227%. But Brazil’s high interest rates of around 12% make borrowing costlier to service. Last year debt payments ate up more than 6% of output. To let businesses and consumers borrow at less exorbitant rates, public banks have increasingly filled the gap, offering cheap, subsidised loans. These went from 40% of all lending in 2010 to 55% last year.

As the government loosened fiscal policy, the Central Bank prematurely slashed its benchmark interest rate in 2011-12. This pushed up inflation, which is now above the bank’s self-imposed upper limit of 6.5%, and way above its 4.5% target. The interest-rate cut has since largely been reversed. The Bank’s monetary policy-makers meet today and will likely raise the rate again, to 12.5%, its level before the decision to cut. A deficit of macroeconomic rigour went hand in hand with a surplus of microeconomic meddling: the government pursued a clumsy industrial policy and shortchanged the private sector, for example by insisting on absurdly low rates of return on concessions to run infrastructure projects. Small wonder confidence slumped among businessmen.

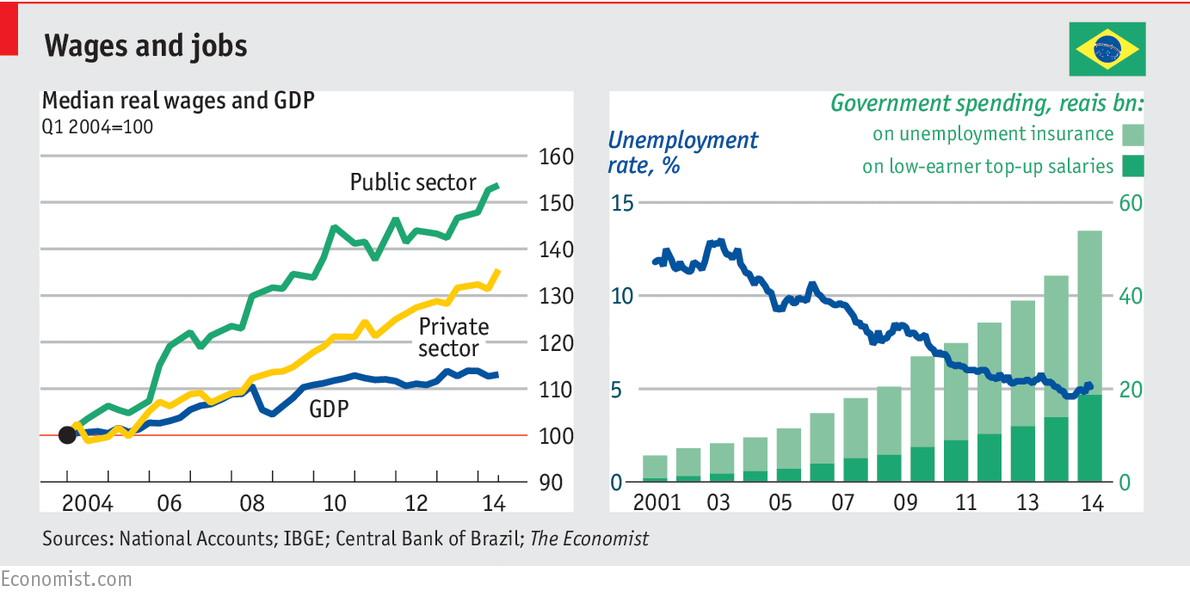

Red tape, poor infrastructure and a strong currency have rendered much of industry uncompetitive. So consumers have been the main source of demand. A low unemployment rate has pushed up wages. In the past ten years wages in the private sector have grown faster than GDP (public-sector workers have done even better). That allowed consumers to borrow more, which encouraged still more spending. Now the virtuous circle is turning vicious. Real wages are no longer increasing, mainly because Brazilian workers’ productivity does not justify further rises. People are returning to seek work just as there are fewer jobs to go around: unemployment, which has long been falling and dipped below 5% for most of 2014, increased to 5.4% in January.

To improve its finances the government is cutting spending on unemployment insurance (which had risen even when the jobless rate was falling) and on other benefits. Taxes, including fuel duty, are going up. So, too, are bills for water and electricity (two-thirds of which is generated by hydropower). The point is to reduce demand following a record drought in 2014 and to correct a policy of holding down regulated prices to keep inflation in check (and voters happy). Because of these increases, inflation soared to 7.14% in the year to January.

All this is hurting disposable incomes, a big portion of which are spent paying back consumer loans taken out in the good times. Consumer confidence has fallen to its lowest level since Fundação Getúlio Vargas, a business school, began tracking it in 2005. The government has no money to boost investment. Petrobras, the state-controlled oil giant and Brazil’s biggest investor, is in the midst of a corruption scandal that has paralysed spending: the forgone investment may reduce GDP growth this year by one percentage point. It is hard to see where growth will come from.

Worst of all, Ms Rousseff’s policy levers are jammed. She cannot loosen fiscal policy without precipitating a downgrade of Brazil’s credit rating. Nor can the Central Bank ease monetary policy. That would once again undermine its credibility—and weaken the currency. A depreciating real, which has fallen 6% against the dollar compared to a month ago and is now at a 10-year low, pushes up inflation? it also makes Brazil’s $230 billion dollar-denominated debt dearer by the day. Ms Rousseff cannot bring Brazil’s animal spirits back to life with more spending and lower interest rates. She can only hope that her return to economic orthodoxy will do the trick. It may take a while.